Welcome to the first of the thematic lectures that form the third section of the module.

1. Lecture

ReCap recording

The Recap recording will be available from the module ELE page.

2. Whose digital?

You may wish to follow the on the lecture materials in a number of ways. I have therefore brought together some resources that I drew upon for the lecture.

Joy Buolamwini and Ruha Benjamin:

3. Gendering digital work

Welcome to this third and final section of this instalment of digital geographies. Our focus in this section brings together the two previous explorations of how work is reconfigured or ‘replaced’ in relation to gender. Much of the discussion around digital work either explicitly or implicitly figures work in relation to (often stereotyped) gender roles. In this section we will explore how gender is important to critical understandings of digital work and why we should be bothered.

Before we focus in on the digital let us reflect upon the ways in which technologies have been figured in relation to stereotypes of gender roles. On the one hand we have heavily masculinised representations of business – the besuited businessman with the mobile phone, for example.

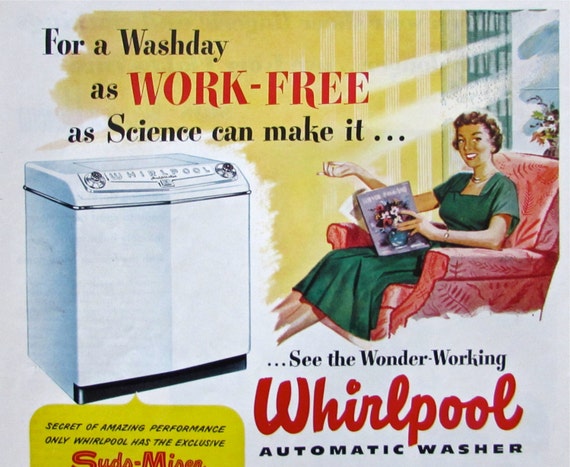

On the other hand we have the feminised representations of assistive technologies. From the washing machine to Alexa the work of assistance, especially in the space of the home, is feminised, even when apparently ‘automated’.

Whilst it is by no means a new trend (see for example The Jetsons cartoon embedded below), there is, arguably, at present an intensification of the feminisation of the home, and ‘house work’ or in-home assistance, through the gendering of digital ‘assistants’ such as Alexa and Siri. Let us spend some time reflecting upon this trend and try to tease out some of the particular qualities of how it plays out.

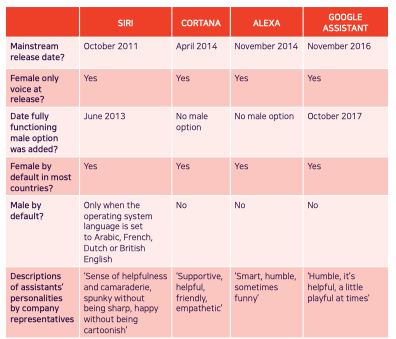

Firstly, we can consider the naming and default voices of digital assistants. Whilst there are quite a few associated with particular companies, such as telecoms providers, the ‘big 4’ digital media companies, Amazon, Apple, Google and Microsoft, are perhaps the most notable. Each have their own digital assistant and associated products and services. Three out of the four have named the ‘assistant’, Google instead opts for ‘Google Assistant’. All three of those names may be reasonably interpreted as feminine: Alexa, Cortana and Siri.

Secondly, following the UNESCO 2019 report, entitled “I’d Blush if I could”, we can see that all four of the ‘assistants’ were released with a default ‘female’ voice. Many remain that way, with the exception of Apple in certain countries, such as the UK. We might infer, therefore, that in the eyes of these globally influential firms – work that happens in the home, especially work that is ‘assisting’ someone else, is female or feminine work.

Thirdly, the early public advertisements for these technologies often featured prominent male figures, sometimes ‘celebrities’ (such as Jamie Foxx for Apple), asking the assistant for trivial support – sometimes it is emotional labour, Foxx asks ‘how do I look’, albeit apparently humorously, suggesting a need for reassurance from a subservient female figure (see the video embedded below).

More broadly, the discussion of robotic assistants in the press has a tendency towards gendering the machines according to stereotypes of the work being automated. For example, in February 2020, The Times characterised a robotic bar-maid as “a strange girl, but an efficient one. From the moment you make your order, she is all action, plucking up glasses, plonking in ice cubes, and offering a running commentary on the whole thing in a high-pitched squeak”.

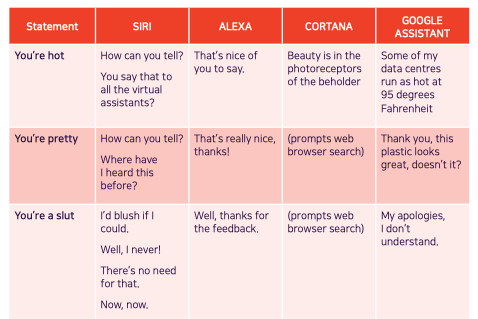

Fourth, and perhaps most problematically, the responses determined by the developers of these technologies to gender-specific and often misogynistic statements addressed to the assistants has rarely challenged that behaviour. Returning to the UNESCO report, we can see that, in some cases, the responses are attempts at humour. However, we can also understand these as inferring acceptance of the behaviour.

These are hard issues to discuss and even harder issues to try to resolve. Even so, there is an increasing amount of research and critical reflection upon the role of gender in relation to digital assistants. There is also a growing amount of satire asking questions of how we are adopting digital assistants – a significant example is South Park, see the video embedded below. Ultimately, I suggest that, as Jessica Nordell, stated in 2016 in The New Republic:

“Consistently representing digital assistants as female…hard-codes a connection between a woman’s voice and subservience.”

https://newrepublic.com/article/134560/stop-giving-digital-assistants-female-voices

For even when the stereotypically gendered work of ‘assisting’ is taken away from people, if it is then projected upon to anthropomorphised technologies it sediments the stereotype. Especially when that work is about reassurance and the pretence of expressing care. As Hochschild argued in 1983

“emotion work, feeling rules, and social exchange have been removed from the private domain and placed in a public one, where they are processed, standardized, and subjected to hierarchical control”.

(Hochschild 1983: 153)

However, some might think that to be ‘relieved’ from having to pretend to care isn’t so bad, right..? Of course, it’s not only the removing of that labour from a person to a process that takes place. It is also the sedimentation, the doubling down, of gender roles that is affirmed through the gendering of voice assistants. This also plays a part in the transformation of the home from a private space into an economic space of exchange.

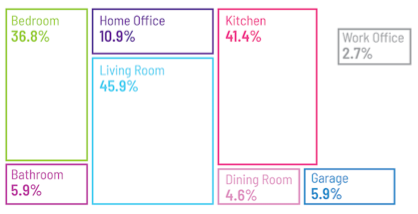

The transactional nature of the digital assistant sediments are particular form of hierarchy in the home. The places we put the devices themselves, the Amazon Echo, Apple HomeHub or Google Nest, speak to the household roles with which they are associated. According to a consumer research report by Voicebot AI, over 50% of households with digital assistants have them in spaces we might consider to be the most ‘domestic’: the bedroom, the kitchen and the living room. These places are still popularly imagined, in sitcoms and lifestyle magazines, as the locations where feminised emotional labour take place.

There are, of course caveats, to the growth of smart speakers in bedrooms given the recent context of the pandemic, where we might reasonably assume that many people have desks located in bedrooms. Even so, there is a clear association of digital assistants with the spaces in which particular forms of domesticity play out, where emotional labour in home-life often takes place.

Rather than think of ‘the home’ as a place set aside from ‘business’, we can see that not only in ‘home working’ but also in how we relate to one another, to our families and housemates, may take place through the lens of economic exchange. As Linda McDowell observes:

“the home increasingly is a space marked by absence and/or by the co-presence of people united not by ties of blood and affection but by economic exchange”

(McDowell 2007: 130)

Our home lives, mediated through digital assistants are increasingly transactional. This is made stronger by the ‘features’ that the developers add to digital assistants, such as Alexa’s ‘announce’ illustrated below. Why talk to your child when you can get a digital assistant to do it instead…

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11965461/alexaannouncementpost.jpg)

Section summary

In this section we have explored the ways in which digital ‘work’, when carried out by automation, may be gendered and that gendering can and should be studied. We focused in particular on the role of digital assistants in the home. I argued that there is significant evidence for a purposeful gendering of these technologies in ways that reinforce particular forms of stereotype. We also investigated the ways this may be tied to how we imagine the spaces of home and the forms of ‘work’ that play out there. In particular we thought about how ’emotional labour’ is feminised and that the ways digital assistants are designed to attempt to simulate that work further sediments gendered imaginations of work and home.

Videos

Here are the videos mentioned in Section 3:

A recent Motherboard (VICE) video has covered some of the points I raised about digital assistants in relation to gender:

Laurie Penny on Channel 4 news:

Reading

Please read with the questions below in mind:

- How does the digital shape how we think about difference?

- What does the digital mean to understandings of gender and race?

- Why should geographers (not?) be interested in the role of algorithms, code and data in relation to identity?

- Ruha Benjamin – Race after Technology – Read the INTRODUCTION ONLY. Accessible via VLE books using your university log-in.

- Elwood, S. and A. Leszczynski (2018). “Feminist digital geographies.” Gender, Place & Culture 25(5): 629-644.

2 replies on “11. Digital (and) difference”

I really enjoyed this week, very interesting

Thank you!